The Cell... Reimagined

27 December 2014I’ve been obsessed with biology ever since I was a kid. It started all the way back from the time when I had to make regular visits to the cardiologist — one of the side effects of being born with a serious heart defect. My heart defect has (thankfully) since recovered, but those visits had a lasting impression on me. I’d always be interrogating my cardiologist when I walked into his office, pointing to his nifty model of the human heart and asking him question after question. And as I grew up, biology remained to consume a large portion of my active curiosity and imagination.

But after coming to MIT, I began to become slightly frustrated with with the approach towards traditional biological research. I had worked in biomedical research laboratories since the age of 14 and served as the lab manager for a microbiology research group at San Jose State University, so I had been exposed to a huge volume of research while in high school. Through all my experiences, I found that traditional biologists treated the cell like a black box, resulting in a rather standard operating procedure:

1) We perturbed the system in certain ways

2) We measured some output

3) We made inferences based on the observations

And while this process has been fruitful over the past few decades, this meta-perspective left me wondering if there was a different way of approaching biological systems.

Engineering Biology

Evolution has always tackled biological systems in a very unique way. Instead of inference, evolution uses induction. Evolution uses the cell as an engine for natural creation, and this realization prompted me to wonder whether we could take the same approach.

Just as silicon became the major vehicle of creation and production in the 20th century, I believe that the cell will soon become the major vehicle of creation and production in the 21st. But this shift in approach will entail significant challenges.

The story of computer systems is one of forward engineering — a human-controlled developmental path. We have the blueprint. Our specifications and standards can be clearly written down and comprehended. We built and control every piece. We understand it.

Image provided by the MIT Synthetic Biology Group

Engineering the cell is a completely different cookie. The evolutionary path is barely understood. We are only beginning to understand the blueprint — the specifications and standards are still shrouded in mystery. It’s a beast we have yet to tame.

But I posit that, maybe, it isn’t necessary to completely understand the cell in order to engineer it. And, maybe, an engineer’s approach to the cell will help us put together pieces of the puzzle we wouldn’t have been able to understand otherwise.

Biological Abstractions

Borrowing generously from the fields of electrical engineering and computer science, I argue that redesigning biology requires the design of appropriate biological abstractions that simplify the engineering process.

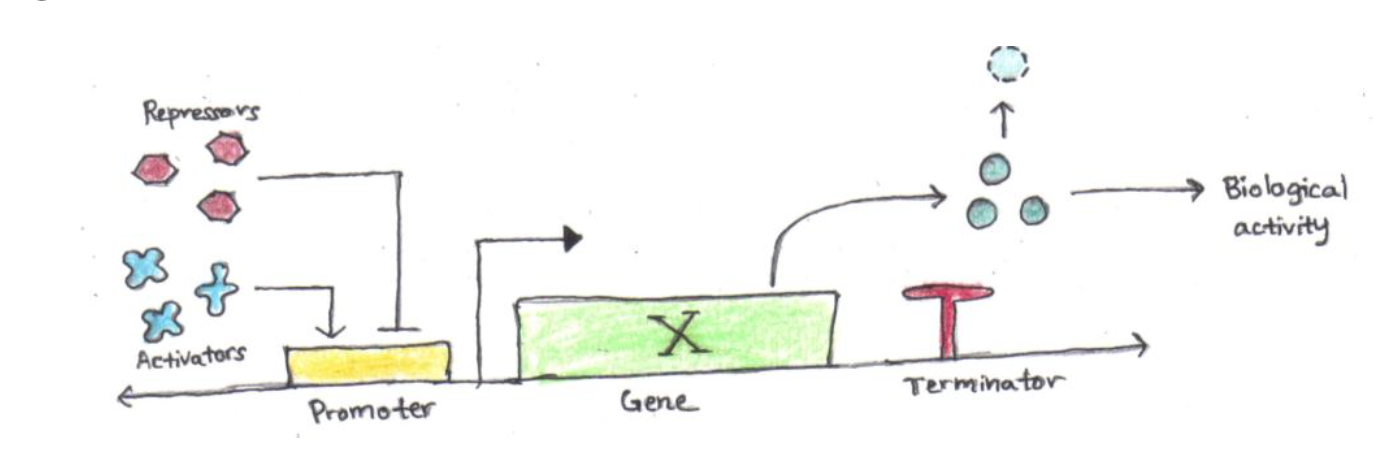

For those new to the field, I present here a simplified view of a low-level genetic unit — a singular gene and corresponding regulatory elements:

A basic unit, consisting of a promoter, protein-coding region (gene), and termination sequence

This unit consists of a protein-coding region, which produces biological activity when transcribed by RNA polymerase. The transcription is regulated by a promoter region, which binds to activators and repressors which control the accessibility of the gene to RNA polymerase. Finally, a terminator immediately follows the protein-coding region to trigger RNA polymerase to complete transcription and fall off of the DNA strand.

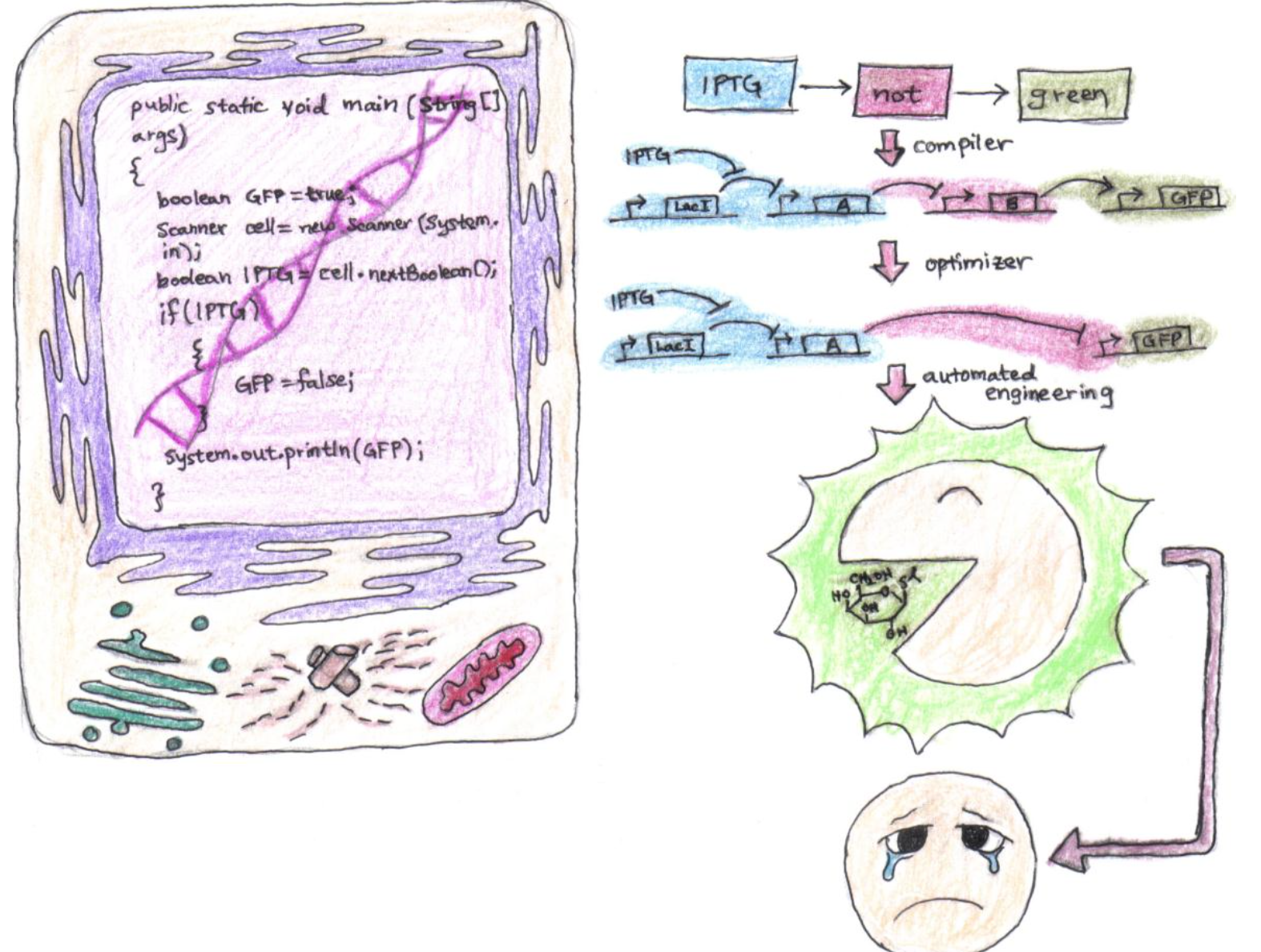

Such building blocks could form the form the foundation of more complex “genetic circuits.” Consider for example, a programming language in which a compiler takes high level descriptions of genetic circuits and turns them into low level instructions For instance, one could imagine a series of two linked units, A and B, where the protein product of unit A binds to the promoter of unit B, thus modulating its expression. The figure below shows how one would implement the high level instruction IPTG → NOT → GREEN.

A Java library, specialized compiler, and optimization routine that illustrates biological abstraction

Each of the symbols IPTG, NOT, and GREEN, correspond to specific pieces that are linked in series as described. The IPTG module consists of two genetic units, one that constitutively expresses the protein LacI (a protein inhibited by the small chemical IPTG). LacI inhibits the transcription of A from the second genetic unit of the module. The result is that in the presence of IPTG, protein A is produced. The NOT module constitutively produces protein B, but it’s expression is inhibited when protein A (the product of the previous module) binds to its promoter region. And lastly, the GREEN module expresses GFP when protein B is bound to its promoter. The result? In the presence of IPTG, protein A is no longer expressed, the level of protein B rises, and consequently, GFP is produced.

But clearly, this is a little verbose, and just as modern computer language compilers optimize the translation of high level code to low level instructions, an optimization routine would be able to determine that we could remove the NOT module altogether, and exchange the GREEN module’s promoter with the NOT module’s promoter so that protein A inhibits the expression of GFP. Operationally, the result is the same, but the system is stabler, and we have reduced the propagation and contamination delays (extending the EE/CS analogies). Finally, the build process would result in the automated engineering of a cell line housing this construct, enabling the full translation of code to functional genetic circuit.

By leveraging the inference techniques that have been explored for decades, testing new parts and modules, and evaluating putative circuits through whole cell model computational models (such as the one released by the Covert Lab at Stanford University), we may soon be able to reliably build complex genetic circuits to perform arbitrary computation.

Next-Generation Biosensors

Probably one of the most interesting applications of a biological programming language is the ability to build custom biosensors. Cells have specialized in sensing and responding to their environments over billions of years, making them particularly versatile at transducing environmental signals. As a result, biosensors have the potential to outperform conventional chemical tests for applications such as pollutant detection, disease diagnosis, etc.

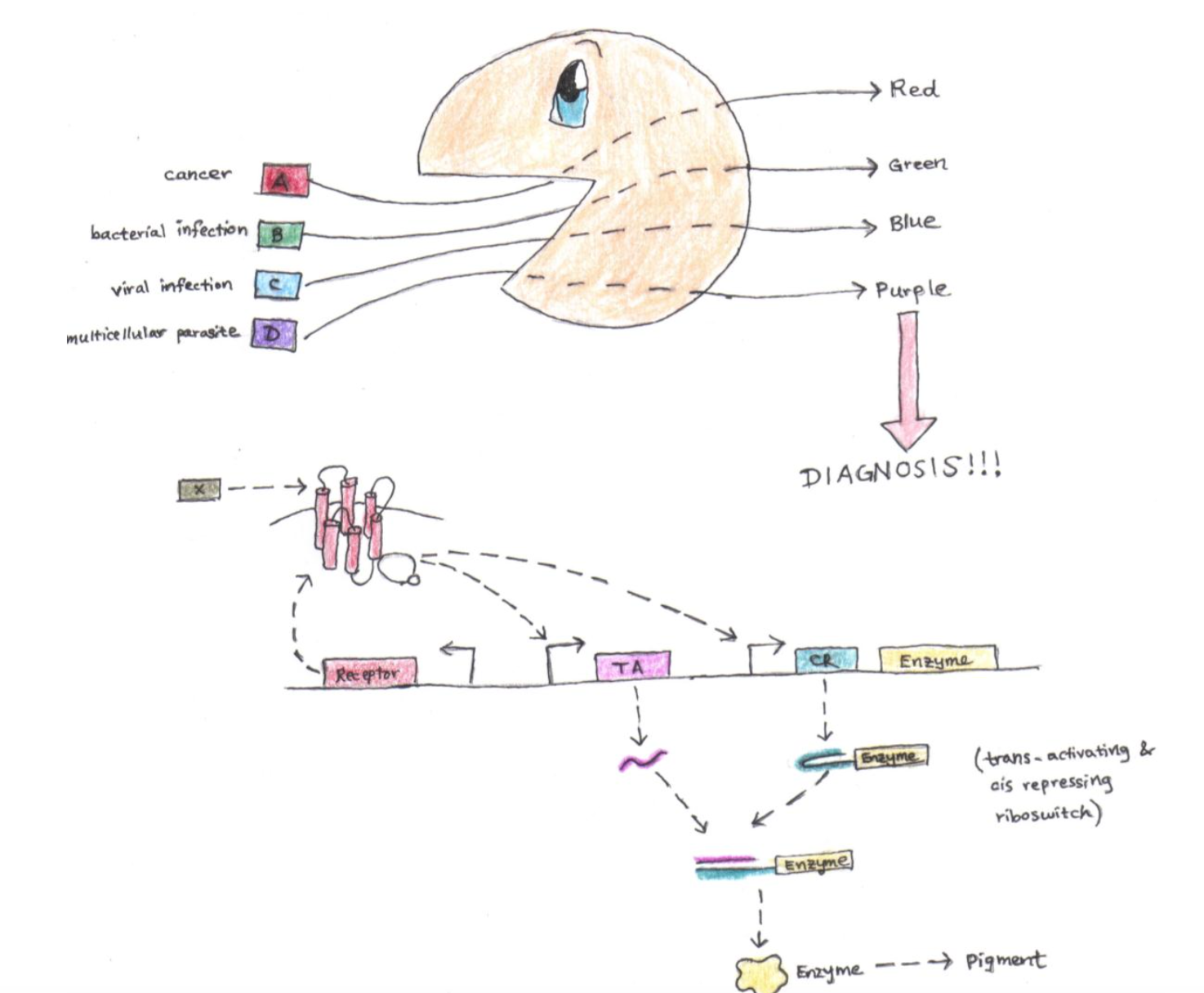

Concept probiotic biosensor for monitoring colon health

Biosensors traditionally consist of two basic modules: a receptor module for recognizing compounds and a transducer module for reporting the signal. In a future where biological parts are plentiful, this division of labor makes it relatively painless for an engineer to make increasingly complex biosensors. For instance, an engineer could load a single cell line with orthogonal receptor and transducer module pairs, endowing it with specificity for more than one signal.

One could imagine using the above strategy to engineer yeast to monitor the health of the GI tract. For example, the yeast could express a receptor for a colon cancer biomarker. Upon ligand binding, the yeast upregulates an enzyme that produces a visible, colored pigment. This pigment would then be excreted and observed in the patient’s stool (as a technical side remark, the illustrated example implements trans-activating and cis-repressing riboswitches to prevent steady-state leakage in the absence of biomarker). One could imagine utilizing orthogonality to enable the same yeast to also recognize infections by bacteria, viruses, and multicellular parasites.

Attacking Cancer with Viruses

Another, rather intriguing, possibility of biological reprogramming is the ability to program cells to die. Apoptosis, biologically programmed cell death, is a hugely important process during normal development and homeostatic maintenance. Being able to induce cells to selectively undergo apoptosis brings up a number of ethical concerns. For instance, a malicious agent could potentially generate super-viruses by loading virus particles with a genetic “kill-switch” circuit.

But if we are able to overcome the ethical hurdles of reprogramming death, this approach may open up a vastly different method of combatting (and, in a future world where we can genetically modify human zygotes, even preventing) cancer.

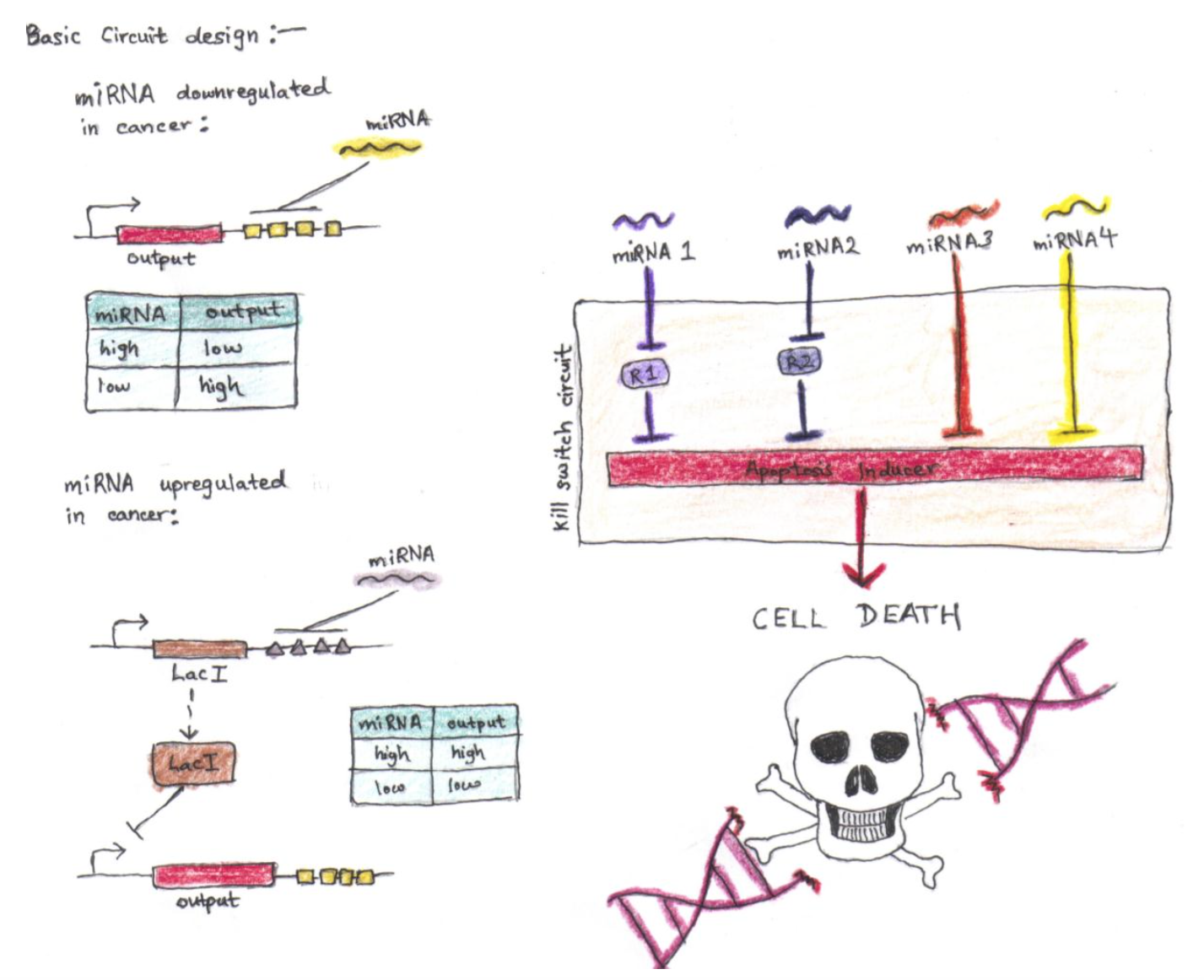

Cancer has a highly altered molecular phenotype compared to the normal somatic cell. Consequently, if we could engineer a “kill-switch” circuit that detects cancerous deviations from the normal molecular phenotype (such as the expression of micro RNAs) and trigger apoptosis when the cell becomes cancerous, we could destroy the tumor before it even has the chance to grow and metastasize. We could load our “kill-switch” into a adenovirus specific to the cancer’s tissue of origin and inject the adenovirus into the patient’s bloodstream.

A concept cancer-targeting scheme adapted from Xie et al., 2011

After thinking about how one would construct such a circuit and consulting the literature, I put together the scheme depicted in the illustration above. It’s somewhat similar to the module developed by the Weiss group, but their paper, published in Science, takes additional, very necessary steps to prevent leakage of the apoptosis inducer. I omit these components because they distract from the core idea and refer interested readers to the original article for the full design.

Conclusions

This is really just the tip of the proverbial iceberg in a field so cutting-edge that it’s changing every single day. I would love to keep writing, but it’s nearly 3 AM and I’d probably bore you if I went any longer. But if I haven’t put you to sleep yet and you’d like to talk more, please email me at [email protected]! I love hearing new ideas ❤

This article is cross-posted on Medium here