Genetics as a Social Network - A Data Scientist's Perspective

18 January 2015Data science and biology have never really mixed well. And in retrospect, it’s pretty understandable why. Biology and medicine have their own lingua franca, which makes for a pretty steep learning curve. People who thrive at this intersection not only have to be in tune with the fundamentals of biochemistry and genetics, but also need to be mathematically adept and strong algorithmic thinkers.

The Data Science and Biology Divide

For decades, we’ve gotten away with computer scientists sticking with computers and biologists sticking with genetics. But things are rapidly changing, and there’s a growing need for people who can bring a data-driven approach to medicine. The advent of modern high-throughput biotechnology has brought upon a data deluge that has completely changed the field’s landscape. For example, a binary alignment file for a single human genome could easily amount to hundreds of gigabytes or terabytes of raw data. Without data science, we risk missing out on valuable insights that could fundamentally change how we deliver medicine.

Modern genetics is a clear example of where data science is already beginning to make huge impacts on our understanding of biology. Traditional biologists have nearly always approached biological systems from a highly simplified, focused perspective. We’ve tried to analyze single genes at a time, often isolated from the larger context in which they exist: protein A upregulates protein B which downregulates protein C. That’s all there was to it.

How biologists used to think about biochemical pathways

The Social Graph of Genetics

But in reality, genetics is much more complicated than that. A single protein could have its expression be modulated by tens of upstream regulators (called transcription factors). And in turn, the same protein could affect the expression of hundreds of other proteins. In a sense, you can think about a cell’s genetics as a huge social network. The fact that protein A directly regulates protein B is analogous to person A following person B on Twitter. So, quite surprisingly, the same techniques you might use to analyze a user’s Twitter network to get them to click an advertisement are also applicable to analyzing a cell’s regulatory network to diagnose disease and design new therapies.

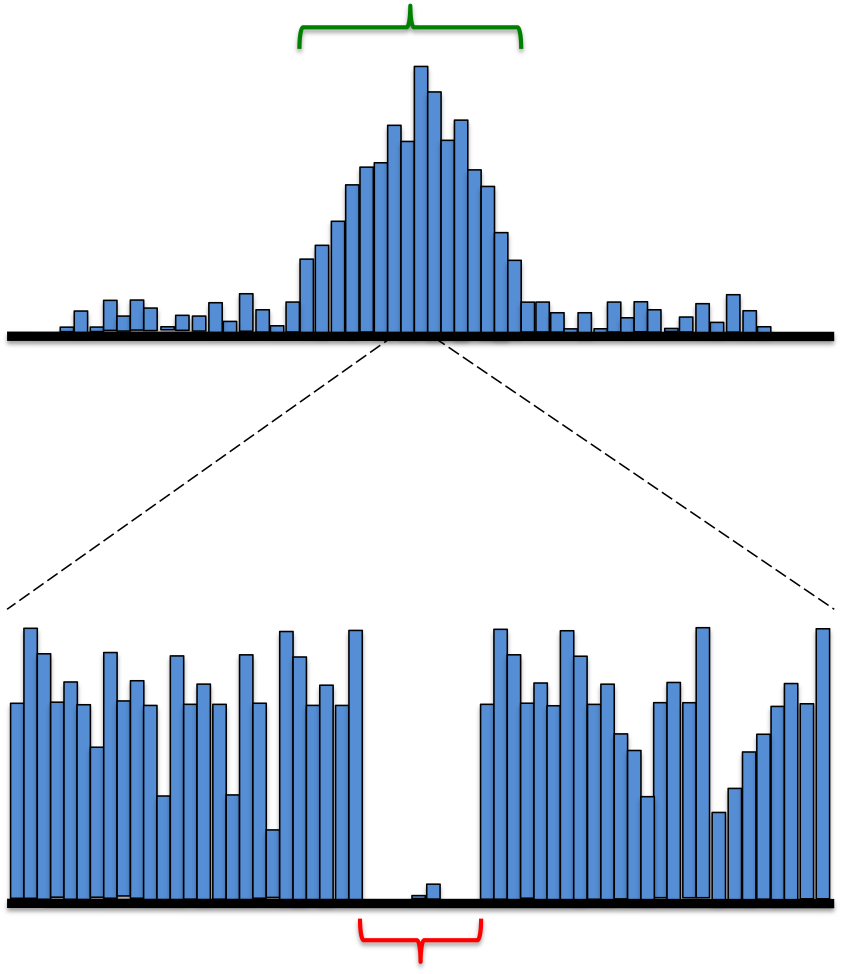

But how exactly do we interrogate these relationships? How do we even know that protein A regulates protein B in a particular cell type? This is where high-throughput biotechnology comes in. Over the past couple of years, researchers have pioneered a technique called DNAse hypersensitivity, which helps us infer these key relationships. In addition to having a region that directly codes for a protein, a gene also has a number of upstream sequences that are bound by regulatory proteins that control its expression. Essentially, the DNase hypersensitivity technique takes advantage of the fact that DNA, for the most part, is packaged very tightly except around these very specific regulatory sequences. As a result, when the DNA is exposed to a DNA digesting enzyme, it is mostly cut at these loosely-packed and exposed regions. The only exception is the small tract of nucleotides that are directly bound to a regulatory protein. These nucleotides are protected from digestion, resulting in a very clear transcription factor footprint.

Histogram showing frequency of DNAse digestion at each location, with a characteristic hypersensitivity site (green) and corresponding transcription factor footprint (red)

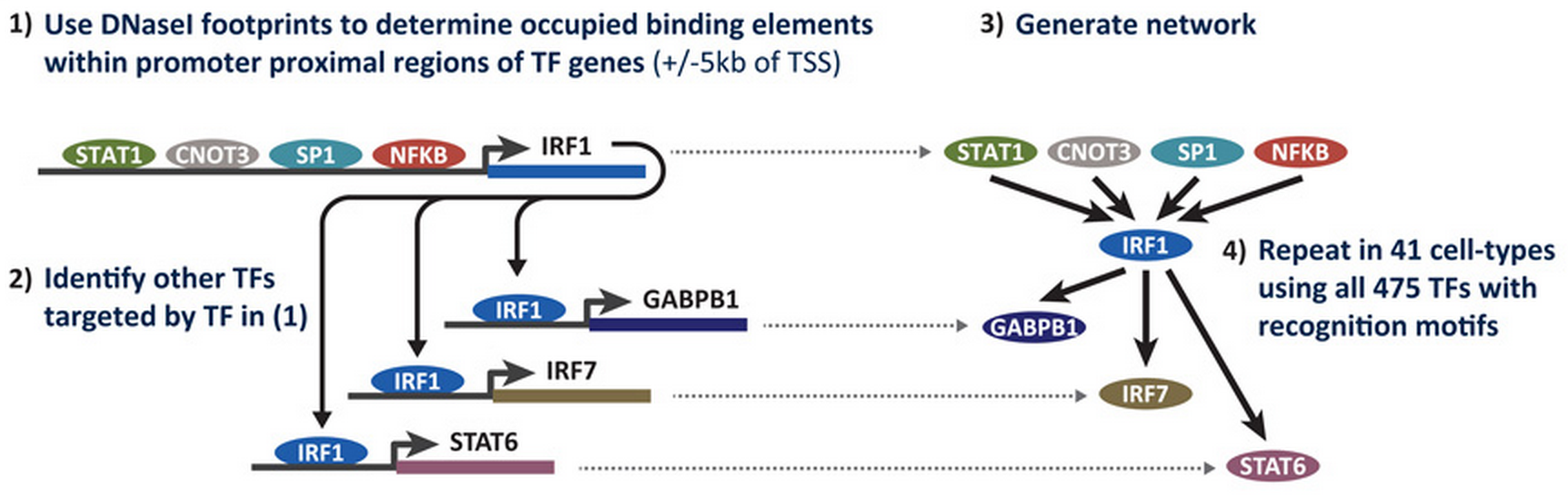

We can then take the DNA sequences of the transcription factor footprints associated with each gene and predict the proteins bound to these regulatory regions using a database such as TRANSFAC. This procedure enables us to reconstruct the genetic regulatory networks at play in every cell type in the body:

Algorithmically generating a cell's regulatory genetic network from footprint data. Figure borrowed from Neph et al.

Applications of Regulatory Network Reconstruction

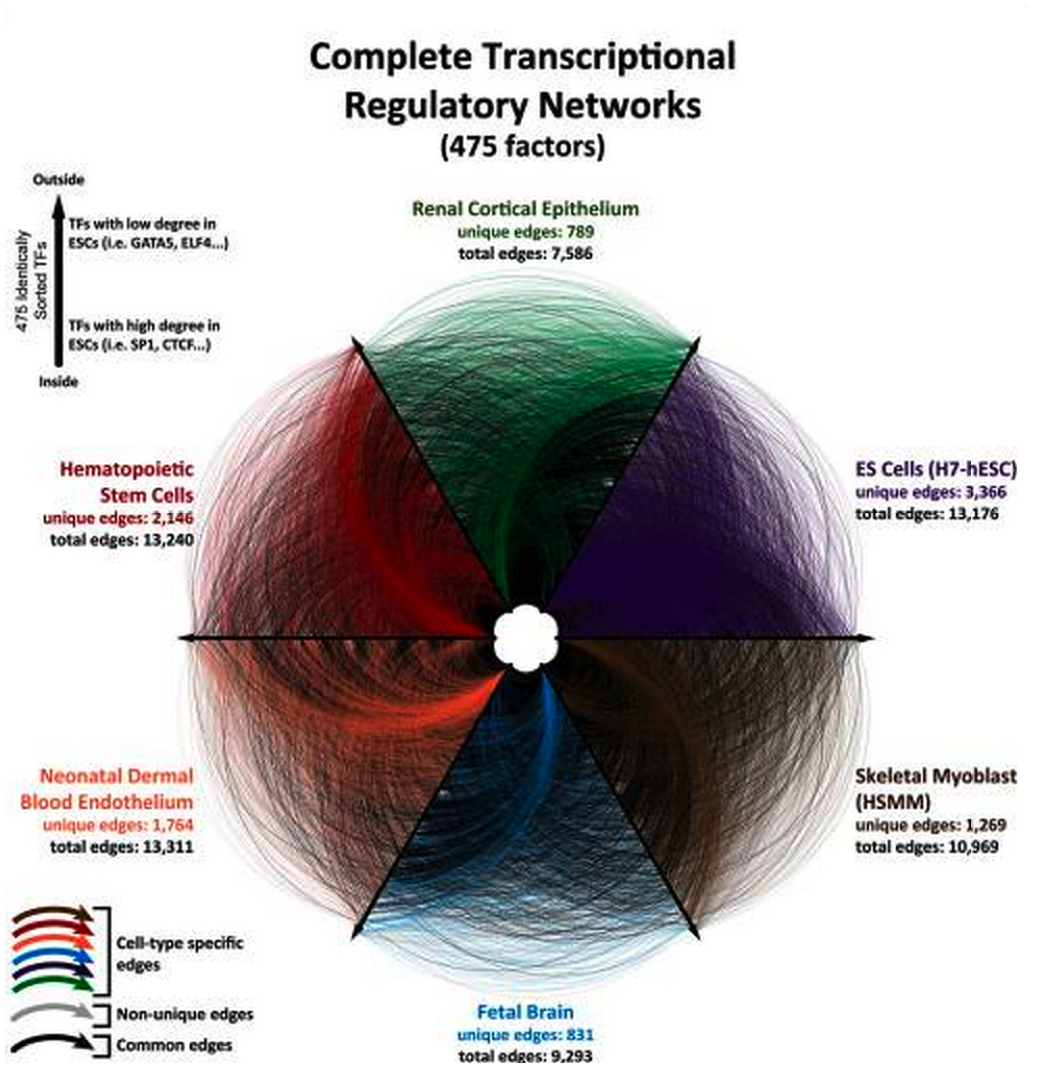

This has a huge number of important applications. For example, this data could be used to understand the foundational differences that differentiate difference cell types. Concretely, this could very significantly inform drug development by allowing researchers to predict how a drug for Alzheimer’s, for example, might have side-effects on the patient’s heart or kidney.

Comparing the regulatory networks in various cell types in the human body. Figure borrowed from Neph et al.

Moreover, my current research involves constructing these networks to compare humans to laboratory model organisms such as mice, rats, and chimpanzees. These comparative models could help us figure out why certain drugs work well in animal studies but fail miserable in clinical trials. Every single year, approximately 95% of drugs fail to obtain approval, and understanding these contextual differences could potentially save billions of dollars in wasted resources.

Conclusions

With petabytes of data being produced every single year, biology and medicine need data science now more than ever before. Undoubtedly, data will shape the future in ways that we can only begin to imagine.

If you want to talk about how to hack biology and medicine with data, please shoot me a line at [email protected]! I'm always open to discussing cool ideas ❤

This article is cross-posted on KDNuggets here